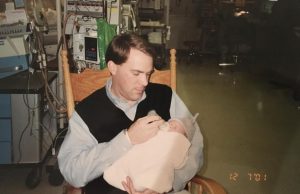

Me, Ava Bidner, seconds after I was born on Dec. 7, 2001.

In Response To. . .

This story was originally written for an AP language class in response to an article from The New York Times titled “When An Abortion Doctor Becomes a Mother”

November 23, 2019

Dear Dr. Henneberg,

My name is Ava Bidner, and I am a 17-year-old senior in high school. I recently read your article in The New York Times titled “When An Abortion Doctor Becomes a Mother,” and after rereading it several times, I felt compelled to write you this letter and make an effort to further open the dialogue about this controversial topic, as you have through your article.

First, I would like to sincerely apologize for the insensitive and insolent words of the protester you spoke of. Hearing stories about people like this man who clearly have no desire to foster understanding with others or actually begin a conversation nearly brings me to tears. I am deeply sorry for his offensive manner of communication, and I truly hope that you do not allow this one man to affect your view of all pro-life supporters. Yes, I am pro-life, and I am also a devout Christian, but I can tell you with confidence that we are not all like this bitter, disrespectful protester. Reading the words “Repent! Repent, baby killer!” makes me nauseous and causes me to realize how profoundly divided we are and how much more humility and mutual respect is needed to restore even the most basic foundation of a relationship.

Furthermore, I respect your decision to become a doctor, and I know how much dedication, hard work, and time you have undoubtedly poured into your education and career. Although I am only a senior in high school, I have attended several programs at WashU medical school, am currently volunteering in a hospital weekly, and have shadowed several doctors in the OR. I plan to be on the pre-med track in college next year with the hope of becoming a neonatologist one day. I am already aware of how much incredible devotion is necessary to succeed in medical school and become a doctor, so I must commend you for attaining such ambitious goals, and I also appreciate your efforts to improve women’s health and assist them in the difficult task of planning for a family. Lastly, I also sincerely agree with your statement at the end of your article: “Everything is messy: the work of doctors, the work of mothers, and the love of each one of us for our children.” There is no doubt we live in an utterly broken world, and your claim encompasses the unfortunate reality of our relationships and careers which often must survive under harsh and adverse circumstances.

However, speaking candidly, your article also led me to mourn the state of our society; I am concerned about the loss of morality in America today, and I am distressed because we seem to place more focus on the issue of rights and freedoms than on compassion and life. Although you made rational arguments through your experiences and stories in your article, I must respectfully disagree with your opinions regarding maintaining boundaries, your assertion that the connection between your work as a mother and as a doctor is “a symbiosis, a harmony,” and your claim that “somebody has to do the work.”

While I completely agree with the need to maintain boundaries between your work and your personal life, and I also respect the fact that you have actual experience with this in the medical field while I do not, I do not believe your perspective of drawing these boundaries is realistic. As you write, “If compartmentalization doesn’t come naturally, it’s beaten into you in training. . . You have to maintain some boundaries. You can’t let it bleed over, you’ll never survive.” I believe this applies to most jobs; whether someone is a politician, a teacher, or a doctor, he or she must make a conscious decision to avoid bringing work home everyday or bringing personal matters to work. That being said, there is a clear distinction between allowing your work life to remain at the office (or in your case, the clinic) and not actually viewing your patients as human beings, and yes, I’m referring to both the mother and the baby. As an INFJ and an intensely sensitive person, I understand the necessity of establishing these boundaries and maintaining them. If I do not do this, I tend to take other people’s worries and emotions on my shoulders constantly, and living with the weight of not only my own but also dozens of others’ issues does not work for extended periods of time. But I believe the boundaries you are referring to are the boundaries between a “baby” at work and a baby in any other part of your life. Your description of your work proves this: “We routinely perform procedures well into our patients’ second trimester, when the fetus is well-formed and easily recognizable as humanlike, even ‘life’-like. Baby-like.” I must ask you, why do you use the words “baby-like?” If your baby had happened to be born premature at 26 weeks (the end of the second trimester), would you have held your brand new little girl for the first time and described her as “baby-like” to your friends and parents as you announced her birth? I would venture to guess that you would not. Most proud and excited parents would describe their new baby as beautiful, precious, and a bundle of joy — and I believe you would do the same. So why do you say that as a doctor, you can draw “a distinction, a boundary, between a fetus and a baby?” You even admit that when you became a mother, you learned there were truly no boundaries. I admire the way you describe this realization: “The moment you become a mother, the moment another heartbeat flickers inside of you, all boundaries fall away.” You are so right. Although I have not experienced this powerful and intense emotion yet, I hope to have several children one day, and I know your description will match my feelings. But I just cannot comprehend how even after giving birth to your daughter and witnessing a miracle, you still are able to build up walls at work and continue to see the babies, the tiny, beautiful humans, at your clinic as merely “baby-like.”

In reality, you cannot separate two of the most essential pieces of your life — your daughter and your work — especially when you are an abortion doctor. You describe the connection between your work as a doctor and as a mother as “a symbiosis, a harmony” instead of a “tension or a contradiction to be reconciled.” This belief may assist you in making it through each day at the clinic, but it simply is not logical or indicative of a consistent worldview. You express your difficulty in denying this fact yourself: “There is the fetus in the dish, the perfect curl of its fingers and toes. Sometimes it reminds me of my daughter — how could it not?” My heart breaks knowing that everyday you go to work and have to stifle the emotions you feel and the connections to your daughter you witness. Wouldn’t life be so much easier if we could carefully divide up our lives into pieces and then store each piece in a box, not allowing it to mingle with the rest of our lives? Unfortunately, life simply does not function this way, and as a doctor who has observed “miscarriages of all types, in every trimester” and allowed these terrifying images to cause alarm during your own pregnancy, I trust that you know this. The “first flicker of a heartbeat” you felt inside you was no different than the heartbeat of any other baby you have ever encountered in your clinic; therefore, I must challenge your claim that your position as a mother is harmonious with your career as a doctor.

Lastly, I cannot support your final statement that “somebody has to do the work.” By “the work,” you are evidently referring to abortion, and while I must concede that an abortion may be necessary in the rare circumstance of saving the mother’s life, I generally do not believe that anyone should have to complete this tragic procedure. Rhett Segall questions your assertion in a comment on your article: “Why can’t ‘the work’ be helping the pregnant mom with nurturing her unborn? Why can’t ‘the work’ be encouraging the community to nurture the unborn? Why can’t ‘the work’ be to remind the father of the unborn to be there and work with the mom? Why does ‘the work’ have to be taking the life of the unborn?” I understand how complex and involved this situation is, and I know that doing “the work” may avoid heartache and lessen the pain in different aspects. Too often, mothers who decide not to abort find themselves falling in love with their babies and wanting to raise them despite the fact that they lack the social structure, financial stability, and basic necessities required to give their child a safe home and a fulfilling childhood. This situation can certainly lead to equal or even greater suffering, distress, and pain for both the mother and the child than if the pregnancy had been terminated. However, Segall makes a valid argument about defining “the work,” and I will add that as a mother who unquestionably loves your daughter with all of your heart, do you not desire for other women to experience the joy of motherhood? After struggling with infertility yourself, do you not want to give other infertile women the opportunity to adopt a baby another woman cannot provide for instead of disposing of the child altogether?

My mom had a devastating miscarriage the year before I was born; she carried her baby, Paige Alma Bidner, who would have been my older sister, for almost 20 full weeks before a tragic stillbirth. The idea of a woman aborting her perfectly healthy baby will always be heartbreaking to my mom and dad who had no choice to keep their precious child. In addition, from the one short article I have read of yours, you appear to be a caring and lovely mother, a supportive wife, and an experienced doctor, and I find it indicative of your morals that you assumed some punishment, some type of “bad karma” as you describe, would occur during your pregnancy because of your work. As you express your anticipation of a tragedy, you not only reveal your most genuine emotions and your deep-seated fear for the future of your pregnancy, but you also hint at the moral dilemma present: “I kept waiting for it, any of it, to happen to me. Nothing would’ve surprised me except a pregnancy that was normal, uneventful, routine.” Although I believe you deserve forgiveness and grace regardless of your actions, your own concern for a penalty as justice for your behavior reveals your true beliefs about abortion and your unease that perhaps it is morally reprehensible.

Overall, I thank you, Dr. Henneberg, for writing with sincerity and conviction in your article, as I hope to have also done in my response. I hope you understand that I am writing you from a place of humility and compassion, not of bitterness or resentment. This discussion is one that is close to my heart — both because of my sweet sister Paige who I will meet in Heaven one day and because of my ambition of working in the NICU with premature and suffering babies in the future. From a place of compassion and concern, I beg you to reconsider the relationship between your work and your personal life as well as the babies you see at work and your own baby because there really are no boundaries. I beg you to consider why “somebody has to do the work.” And I beg you to begin seeing every patient not simply as “baby-like” but as he or she truly is: a baby — and a blessing.

Sincerely,

Ava Bidner